The “White Pine Problem”

Often, during a school visit or a reading, someone in the audience asks about teachers who encouraged or influenced me as a writer. In response, I give credit to my 8th grade English teacher, Norm Wilson; to Kay Herzog, whose high standards in high school English taught me to revise and revise; to Harvey Swados, who taught me about the relationship between writing, work, and life; and to the inimitable Grace Paley and her brilliant skills with voice and dialogue. But this morning, as I rode my bike up a country road in Vermont, I realized that one of the most important influences on my writing was not a writer, but the biologist and field ecologist, Ty Minton.

I met Ty when I was enrolled in Antioch’s Masters in Education program and signed up for his course in Field Ecology. The class I remember best took place on a sunny fall afternoon when Ty told us we ready to solve the “White Pine Problem.” We followed Ty into the middle of a forest populated only by white pines. Before we could ask any questions, Ty told us that the trees had not been planted. “Spread out, walk around on your own, see what you discover about these trees. Why are they here?”

I wandered among the pines, puzzled. If no one had planted these trees, how had they grown in such orderly rows? The pines were large. Their heavy branches, laden with long, soft needles, blocked the sunlight, so there was very little undergrowth—or at least, that’s what I thought. As I ducked under branches and knelt to touch soft moss growing on the north side of a tree, I noticed a few deciduous sprouts—a maple or a cherry seedling yearning for sunlight. The seedlings, I noticed, were about the same age and size.

Aha! I stood up quickly. We’d been reading about old-field succession, where abandoned fields give way to perennial grasses, wildflowers such as ragweed and goldenrod, before tough shrubs such as hardhack or hobblebush move in. In New England, paper birch and white pine are often the next plants to arrive. And after that: mature hardwood forest.

I hurried back to Ty, who waited in the shade of the pines. “This used to be a pasture!” I said. “Exactly.” He smiled. As we spoke, excited exclamations rose from different corners of the forest, as classmates also solved the “problem.”

Though I didn’t realize it at the time, that afternoon marked a turning point. I was studying for a graduate degree in teaching, with a dream of starting a school—something I accomplished a few years later. I’d also written a few magazine articles and co-authored a book on education. But standing beneath the pines, and for weeks afterwards, I wondered if I’d chosen the wrong path. Ecology was then a new field. Should I change direction, become a field ecologist? My science education, so far, had been very limited, so I’d have to start from scratch. Though I stayed for another semester of field ecology, I kept going on the path I’d chosen—but with a difference. Science and nature and the environment became important threads that informed my work with children, as well as my fiction later on.

I remembered Ty’s class a few days ago as I biked up a dirt road in Vermont. I was headed for the house where we lived when I was born. One of my earliest memories takes place in a field across from that house. I was in a hay wagon, pulled by a team of chestnut-colored Belgians driven by our neighbor, Hope Hazelton. I remember the smell of fresh-cut hay mixed with the scent of horse sweat, manure, and Hope’s cigarette; the sound of creaking wheels; the heft of the leather reins when Hope set them into my small hands and let me drive the team.

As I biked, I worried. Was the field still there? The hollow where we lived, once home to dairy farms, has given way to McMansions. Our former house is twice its original size, with a two-car garage and extensive lawn. Many cow pastures are forested now. What had happened to the Hazelton’s field? As I came around the corner near our old house, I noticed a grove of white pines partway up the hill. Ragweed, goldenrod, and Queen Anne’s lace were in bloom below the pines. I slowed down. Were the pines beginning to create a forest like the one we visited with Ty? I kept pedaling and saw a page-wire fence running along the edge of the road. I stopped. The fence also went up the hill beside an old trail. I couldn’t see any animals, but the clipped grass told me that the field is no longer a hayfield—but it is a pasture.

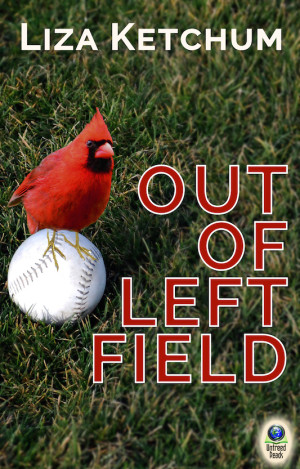

As I biked home, I realized that I never really gave up on ecology or the study of nature. I’ve been an avid gardener all my life. When I taught preschool, I wove science into our curriculum. In my novels, I pay close attention to the natural world my characters inhabit, whether it is a California gold field (Newsgirl), a bluff above the Ohio River in 1828 Kentucky (Orphan Journey Home), or the tides of the Bay of Fundy (Out of Left Field).

And now my writing life is even more focused on the environment. As the earth warms and nature is under assault, I have joined a bee committee in our town, I’ve planted gardens attractive to pollinators, and I’m writing—with two dear, esteemed colleagues—non-fiction books for kids that focus on positive stories in nature. (Stay tuned.)

And now my writing life is even more focused on the environment. As the earth warms and nature is under assault, I have joined a bee committee in our town, I’ve planted gardens attractive to pollinators, and I’m writing—with two dear, esteemed colleagues—non-fiction books for kids that focus on positive stories in nature. (Stay tuned.)

When I work with students, I compare the theme or emotional line of a story to a closet rod, something a story’s scenes and intention can hang on. I also imagine that the theme is like the drone on a bagpipe, the single note that hums below a story’s melody. Fifteen books, many articles, and numerous talks on setting later, I see that a passion for the natural world is a note that thrums through everything I write. So the white pine class wasn’t a “problem” at all. It was an opening and a reminder that writers can benefit from diving into other disciplines—and that great teachers can change a life. Thank you, Ty.

Liza, what is The Life Fantastic about?

Liza, what is The Life Fantastic about?

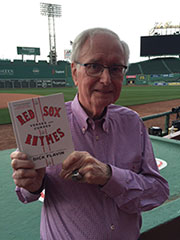

![Back-up catcher Doug Mirabelli was the perfect team player for the Red Sox, doing anything needed -- even welcoming ceremonial first pitch participants in 2002. By U.S. Navy photo by Journalist Seaman Joe Burgess. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.lizaketchum.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/US_Navy_020703-N-7422B-001_Torpedomans_Mate_3rd_Class_Brian_Ryan_Secretary_of_the_Navy_Gordon_England_U.S._Marine_Captain_Israel_Garcia_and_Boston_Red_Sox_catcher_Doug_Mirabelli.jpg)